Historical Reference and Self-Reflection in Recent Latin American Fiction - Jobst Welge - University of Hamburg

- Lecture2Go

- Catalog

- F.5 - Geisteswissenschaften

- Sprache, Literatur, Medien (SLM I + II)

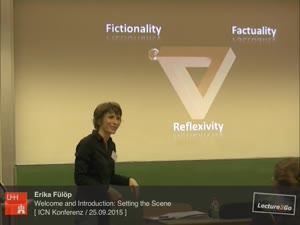

- Fictionality, Factuality, Reflexivity (ICN-Konferenz 2015)

Catalog

Historical Reference and Self-Reflection in Recent Latin American Fiction

A Conference of the Interdisciplinary Center for Narratology

University of Hamburg, 25–26 September 2015

The dominant tone in the literary critical discourse on narratives of the past couple of decades suggests that self-reflexivity became somewhat outdated as postmodernism reached a stage of exhaustion: the novel, after its narcissistic phase, has returned to the story, to the subject, and to a non-ironical and less sceptical approach to history, and it is now concerned again with more serious matters than itself. The implication is that reflexivity goes against referentiality and that it undermines the very possibility of factuality. Linda Hutcheon"s definition of historiographic metafiction as "novels which are both intensely self-reflexive and yet paradoxically also lay claim to historical events and personages" is symptomatic in this respect. But why should, in fact, the combination of self-reflexivity and the reference to historical events – and thus a degree of factuality – be paradoxical?

Meanwhile, reflections on method addressing the conditions of a scientific or argumentative (factual) discourse within the space of that same, not exclusively non-narrative, discourse proliferated in the second half of the past century. Foucault’s Archaeology of Knowledge, Hayden White’s Metahistory, Roger Laporte’s or Derrida’s reflections on writing, to mention only a few, all discuss their own conditions as discourse and activity without excluding a degree of narrativity – but also without turning fictional.

A crucial question in these and other late-twentieth-century metadiscursive texts is to circumscribe the part of fiction(ality) or fictionalizing in the production of discourses which are factual in their aim. The distinction between fact and fiction, between factuality and fictionality, has indeed itself been the object of much recent discussion not only in literary theory but also in philosophy, both analytic and continental. While literary theorists and fiction theorists first hoped to find distinctive traits in the text that helps identify the traces of fictionality and came to the conclusion that these are neither semantic nor syntactic but depend on the pragmatic framework, continental philosophy, particularly poststructuralism, formulated the question primarily in terms of representation and referentiality and the limits of language’s ability to faithfully mediate the world. At the same time, in analytic philosophy logicians have been grappling with the consequences of the ontological difference between fictional and factual objects on logic, its laws and its formalizability. Self-referentiality, on the other hand, and by extension self-reflexivity, poses the problem of the paradoxes it can generate – and reflections on self-referential paradoxes greatly contributed to the development of non-classical logics. As a result, the concept of logical impossibility, which is one reason why certain forms of narrative self-reflexivity in particular are associated with fictionality, has become much less straightforward and also needs to be reconsidered in the context of literary and other narratives.

This conference brings together the perspectives of literary criticism, approaches to other media and analytic and continental philosophy in order to rethink the complex relations between fiction/fictionality, fact/factuality, self-reflexivity and self-referentiality/heteroreferentiality.

---

A Conference of the Interdisciplinary Center for Narratology

University of Hamburg, 25–26 September 2015

The dominant tone in the literary critical discourse on narratives of the past couple of decades suggests that self-reflexivity became somewhat outdated as postmodernism reached a stage of exhaustion: the novel, after its narcissistic phase, has returned to the story, to the subject, and to a non-ironical and less sceptical approach to history, and it is now concerned again with more serious matters than itself. The implication is that reflexivity goes against referentiality and that it undermines the very possibility of factuality. Linda Hutcheon"s definition of historiographic metafiction as "novels which are both intensely self-reflexive and yet paradoxically also lay claim to historical events and personages" is symptomatic in this respect. But why should, in fact, the combination of self-reflexivity and the reference to historical events – and thus a degree of factuality – be paradoxical?

Meanwhile, reflections on method addressing the conditions of a scientific or argumentative (factual) discourse within the space of that same, not exclusively non-narrative, discourse proliferated in the second half of the past century. Foucault’s Archaeology of Knowledge, Hayden White’s Metahistory, Roger Laporte’s or Derrida’s reflections on writing, to mention only a few, all discuss their own conditions as discourse and activity without excluding a degree of narrativity – but also without turning fictional.

A crucial question in these and other late-twentieth-century metadiscursive texts is to circumscribe the part of fiction(ality) or fictionalizing in the production of discourses which are factual in their aim. The distinction between fact and fiction, between factuality and fictionality, has indeed itself been the object of much recent discussion not only in literary theory but also in philosophy, both analytic and continental. While literary theorists and fiction theorists first hoped to find distinctive traits in the text that helps identify the traces of fictionality and came to the conclusion that these are neither semantic nor syntactic but depend on the pragmatic framework, continental philosophy, particularly poststructuralism, formulated the question primarily in terms of representation and referentiality and the limits of language’s ability to faithfully mediate the world. At the same time, in analytic philosophy logicians have been grappling with the consequences of the ontological difference between fictional and factual objects on logic, its laws and its formalizability. Self-referentiality, on the other hand, and by extension self-reflexivity, poses the problem of the paradoxes it can generate – and reflections on self-referential paradoxes greatly contributed to the development of non-classical logics. As a result, the concept of logical impossibility, which is one reason why certain forms of narrative self-reflexivity in particular are associated with fictionality, has become much less straightforward and also needs to be reconsidered in the context of literary and other narratives.

This conference brings together the perspectives of literary criticism, approaches to other media and analytic and continental philosophy in order to rethink the complex relations between fiction/fictionality, fact/factuality, self-reflexivity and self-referentiality/heteroreferentiality.